Cover crops don’t use much extra water, video explains

Central Valley farmers benefit from winter planting – but GSAs must change how they measure groundwater use, Mitchell says

Many farmers have been wary of planting cover crops, despite the proven benefits, because they worry the additional vegetation in their fields and orchards would suck up precious water. But a new video explains recent research showing that’s not true: California fields planted with cover crops over the winter have about the same level of soil moisture.

That adds to evidence that planting cover crops is a good bet for farmers, even in dry and drought-prone areas, according to work by a team led by Jeffrey Mitchell, a professor of UC Cooperative Extension in the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences.

Just as importantly, their work has profound policy implications for the way the state monitors groundwater pumping: The methods local groundwater sustainability agencies (or GSAs) use to measure groundwater use must be updated to account for the benefit of planting cover crops in the wintertime, Mitchell said.

Currently, methods used by local agencies to measure groundwater use can penalize farmers who plant cover crops in the wintertime, unintentionally discouraging this water-saving, soil-building, environment-healing practice.

“When you plant a cover crop, the soil gets improved, and the improved soil ends up capturing and storing more water,” Mitchell explained. “Because of the cover crop, the soil also is cooler, so less evaporation happens… You don’t end up using what these models used by the GSAs say you’re using.”

Ins and outs balance, study shows

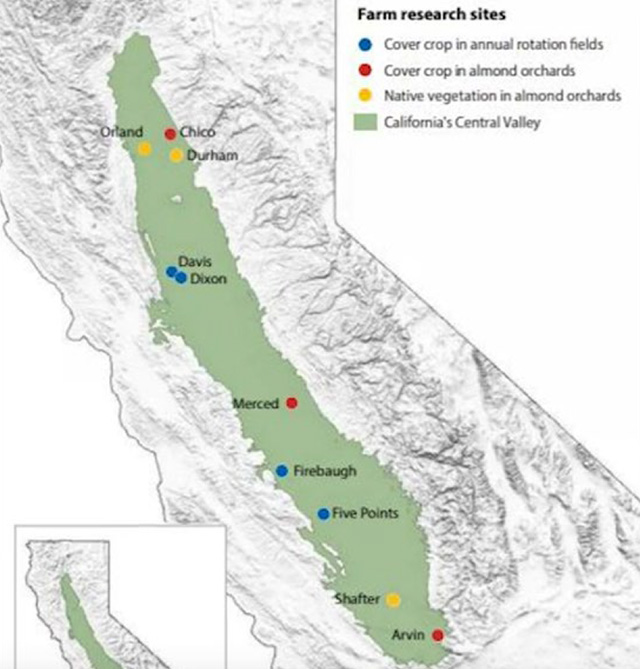

In the video, doctoral student Alyssa DeVincentis, who worked with Mitchell, explains her research over three years in 10 commercial fields in the Central Valley, ranging from Chico in the north to Arvin in the south. She zeroes in on results from two fields that compare soil moisture in areas with and without wintertime cover crops.

“The amount of water cover crops were transpiring on our two fields amounted to less than an inch of water, which is small in the scheme of an irrigation budget for a farm,” DeVincentis says.

The team’s work offers “some of the first numbers on actual cover crop water demands within California’s specialty crop systems,” DeVincentis says.

This work is important because those numbers offer a starting point for regulators and others who are implementing the state’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act and creating local sustainability plans. DeVincentis cautions that models being used need to be more nuanced, taking different conditions into account.

Update planned for almond board guide

The researchers collaborated with another team lead by Amelie Gaudin, an associate professor holding the Endowed Chair in Agroecology. She is looking particularly at the wide-ranging impacts of cover crops in almond orchards. Almonds are an expanding crop in the state, with more than 1.6 million acres planted in 2022, according to the California Almond Board.

Mitchell’s team monitored plots on farms, and collected and processed data in orchards that Gaudin also is studying. Gaudin can add this material to her own analysis, she said. Information on how farmers can reduce cover crops’ potential trade-offs in terms of water use will be added to the Cover Crops: Best Management Practices, a guide that Gaudin led and co-authored for the almond board.

“Farmers face many barriers to planting cover crops and diversifying what they plant in the alleyways” between rows of trees, Gaudin said. “This project shows the power of teaming up with people who have different areas of expertise to tackle those barriers.”

Low-till adds to water savings

The team conducted their research from 2016 to 2019 at sites growing almonds and tomatoes. Colleagues in UC Agriculture and Natural Resources also contributed their knowledge to the research presented in the video. In 2022, ANR recognized them with the “Excellent Team” award, and two articles describing their work have been published in California Agriculture.

Their findings:

- Generally, there were not significant differences in soil moisture between cover-cropped and control fields either throughout or at the end of the winter seasons,

- Combining reduced disturbance tillage, winter cover crops and surface residue preservation led to higher soil water contents than bare surface, non-cover cropped conditions,

- Explanations for these findings are complex and involve the following factors:

1. Generally low evapotranspiration demand during the winter period in the Central Valley.

2. Shading and cooling of the soil surface by cover crops and surface residues resulting in lower soil water evaporation.

3. Overall improved soil health in cover cropped and reduced-disturbance systems, leading to increased soil aggregation, water infiltration and storage.

Because of this complexity, the researchers urged local groundwater sustainability agencies to be cautious about using satellite remote sensing to measure water use during the winter in California’s Central Valley, when cover crops are present.

Currently, those agencies use satellite imagery to detect crops on the ground and, from that information, calculate how much water a farmer is pumping, Mitchell explained. That amount is then subtracted from the allocation the farmer can get during the summer growing season – wiping out the incentive to grow cover crops, Mitchell said.

“Our research shows, it’s much more nuanced,” Mitchell said.

Related links

The 31-minute video can be viewed here.

Media Resources

- Trina Kleist, UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences, tkleist@ucdavis.edu, (530) 754-6148 or (530) 601-6846